Courtesy of Science

The debate and discourse about youth sports specialization and talent identification and development systems never ends — we probably touch on those and related topics at least once a week.

But while there are many compelling philosophies and strongly-held opinions throughout the industry, they are often just that — educated and rational takes, but often based more on anecdotes and common sense than hard data.

That is changing.

A pediatric orthopedic surgeon concluded professional athletes who played several sports as kids may have a greater chance at success than single-sport peers in research released in August.

Now a new study — “Recent discoveries on the acquisition of the highest levels of human performance” — is generating so much buzz that both the WSJ and NY Times hammered out spot news stories.

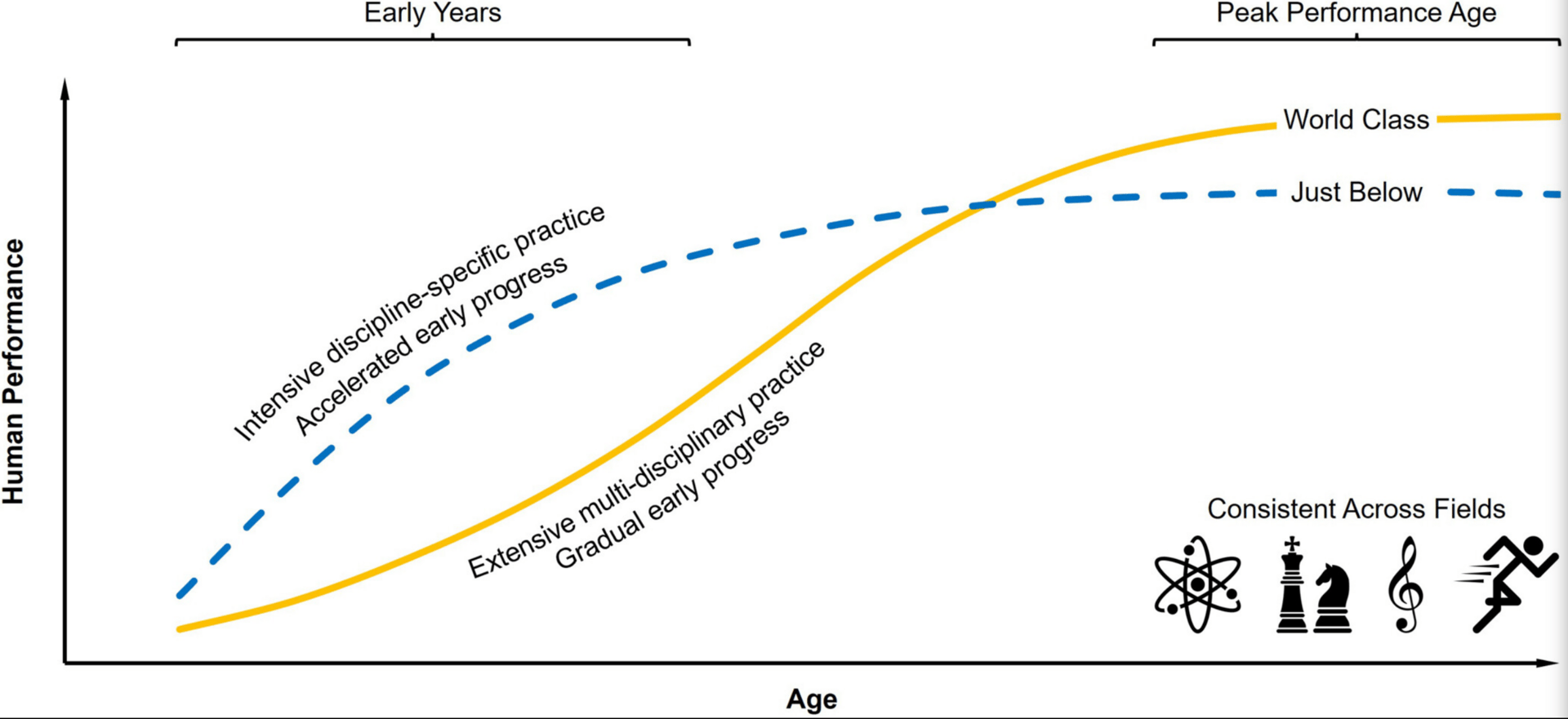

A quartet of American and European researchers examined the development of over 34K top adult performers worldwide across a variety of disciplines — sports, music, Nobel Prize winners, etc. — and found:

Young exceptional performers and adult world-class performers are mostly two different populations over time

Early exceptional performance is associated with extensive specialization practices and fast gains at a young age in a single discipline

Adult world-class performers tended to participate in multiple activities and disciplines as kids and gradually progressed to an elite level in their chosen discipline

Across the highest adult performance levels, peak performance is negatively correlated with early performance.

Per the study:

International-level youth athletes and later international-level adult athletes are nearly 90% different individuals

Higher early performance in a domain is associated with larger amounts of discipline-specific practice, smaller amounts of multidisciplinary practice, and faster early discipline-specific performance progress. By contrast, across high levels of adult performance, world-class performance in a domain is associated with smaller amounts of discipline-specific practice, larger amounts of early multidisciplinary practice, and more gradual early discipline-specific performance progress. These predictor effects are closely correlated with one another, suggesting a robust pattern.

Some caveats: Researchers did not conduct their own randomized studies — i.e. assign and control what participating kids did — and relied on already-existing prospective and retrospective studies.

A un-involved Harvard researcher also told the NYT she would be curious to see the separated results of the data. She hypothesized that while most child prodigies do not reach the top of their field, most top adult performers were likely considered elite to some extent as kids — in other words, a subset of early high performers doesn’t burn out and continues to grow.

My favorite anecdote on the subject comes from Bryce Harper - one of the most celebrated major-sport youth athletes in American history, who lived up to the hype - on a Phillies podcast (36:11 mark):

His thoughts have been echoed by LeBron James and countless others.

Besides the parenting and child development aspects of this (the most important), what does this growing body of research mean for the industry?

2 things:

1) I think we’ve now moved beyond the Tiger Woods-ification of youth athleticism. It’s clear that sort of rigor and focus from such a young age doesn’t create the next world-class superstar. For every Tiger Woods there are 100,000 miserable kids and 1 miserable Tiger Woods.

As this concept begins to take root with parents, those in the industry who have benefited from specialization should consider offering other sports lest they risk losing participation hours.

This is why I’m bullish on club expansion that includes adding more sports. As examples, NY Empire Baseball and True Lacrosse have taken on capital to expand both geographically and into new sports. It turns out that if you can run a solid club business based around principles, you can probably hire quality coaches to offer more than one sport. Sure, there might not be much, if any, cross-over among the athletes in these examples, but I can certainly see a world where multi-sport programs that encourage participation in more than one sport surpass single-sport clubs. Ironically, it sounds like I’m describing rec programs and schools, go figure.

2) Expect cost of participation and specialization, in that order, to be the two topics that dominate youth sports discussion in 2026. These are the narratives that will threaten pockets of the industry.

…

All of that being said, evidence from the study found that it’s OK to have a main thing, but that two having additional activities might be the “sweet spot”. So perhaps the answer is acknowledging the difference between “focus” and “specialization.”

🤳 Follow Buying Sandlot on Social

We’re new— help us build up our social media accounts by following along: